Day 22: Making accessible forms

Today, Vicky Teinaki talks about accessible forms.

Forms are a common part of most people’s lives. We have to complete one when we need something from someone else. And in many cases, such as when interacting with a government department, not completing a form or making a mistake can mean bad things happen later, from getting a fine to missing out on benefits.

Here are some tips for making forms both more usable and accessible, with a few festive examples.

1. Use a question protocol and consider extra access needs

‘Question protocols’ were coined by Caroline Jarrett - though they can also be thought of as an ‘answer protocol’ . They are mentioned in form design guidance for several governments, including the UK, Scotland, and Ireland.

A question protocol makes sure that people designing a form understand what data they are asking people for and why. It suggests that you should only add a question to a form if you know:

- that you need the information to deliver the service

- why you need the information

- what you’ll do with it

- which users need to give you the information

- how you’ll check the information is accurate

- how to keep the information up to date and secure

- if he types this wrong now, if he have a chance to fix this later (for example as a last check before he sends the form, or even after he has completed the form)

- can the input field be set up to use the autofill HTML attribute so that it tries to guess 'Santa' and he can select it

- dyslexic may welcome the chance to talk to someone rather than having to read a lot of text

- Deaf cannot use a callback unless it has some form of text-only option or video relay with British Sign Language (or whatever sign language they speak)

- putting lot of accessible components on a single page can be overwhelming for people with cognitive disabilities - fix this by splitting them up with one thing per page

- not telling people that they will need information from certain documents to complete the form - fix this by telling people at the start if there are things that they must find

- having a lot of optional input fields that are noisy for screen readers and tiring for people with cognitive disabilities - fix this by using filtering questions

- designs being tweaked to be faster to code - for example an autocomplete being changed to a select list

- components being rebuilt in code frameworks and missing some details that were there for accessibility, for example aria fields or autofill

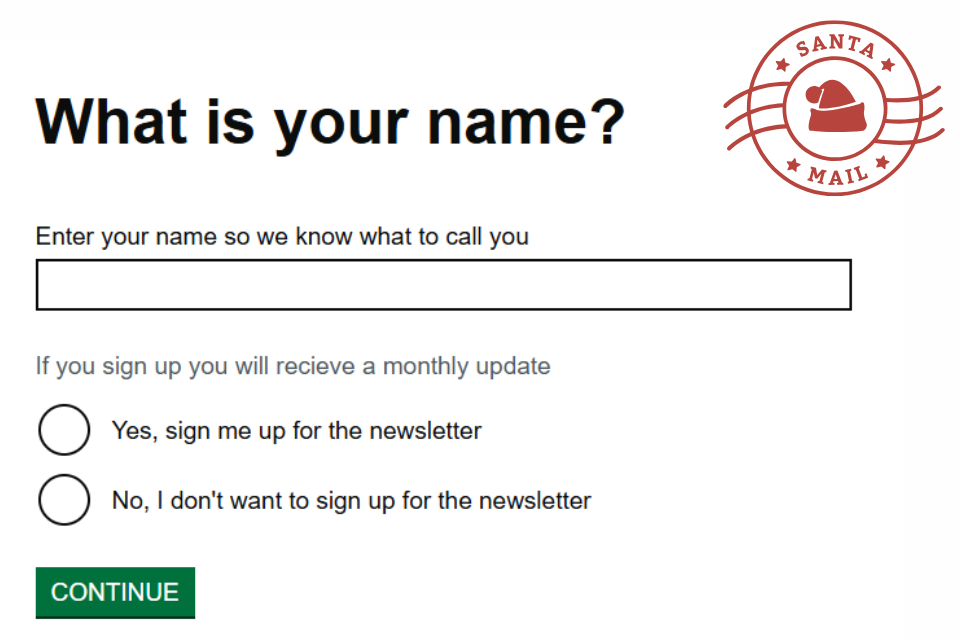

| Question protocol | A newsletter sign up form |

|---|---|

| Answer or data we need | Name |

| Why it is needed | To be able to address the user, to identify the individual users |

| How is is used | Hi, Santa |

| Level of importance (must have, nice to have) | Nice to have |

| What happens if this question has no answer or a wrong answer | A strange interaction with the user |

| Extra questions to ask based on the context |

Extra questions to ask based on the context

Considering what these questions might mean to someone who is disabled can bring up extra challenges with the data you are collecting and questions you are asking.

For example, if Santa trying to sign up for a mailing list on his phone but is struggling to input his name (because of a temporary disability because he has cold hands, or more permanently because he has arthritis), we might consider extra things such as:

2. Understand that different access needs can clash

Some disabled people's needs are partly covered by standards such as WCAG. However, compliance is not enough, as a form can meet for example WCAG 2.2 and have an accessibility statement but not be accessible.

More importantly, people's different types of access needs can vary. For example, if Santa's helpers include one that is dyslexic and one that is Deaf, and they both fill in a form that includes a callback, the helper that is:

Everyone needs some form of option, and part of understanding these needs is figuring out how to balance them all and even choose options that can work for many groups of people (for example chat options for followup can be used by people that also can get phone calls).

The best way to manage this is to make sure that disabled people are involved with the making of your forms, through research, testing and even having them as part of your team.

2. Start with tried and tested accessible patterns

While it’s common and good to use components from a design system in a form, it is possible to use them in a way that is not accessible.

A few examples of this include:

A tried and tested pattern may not work for the context of your form, but starting from it at least means that you can discover original problems when you work with disabled people.

4. Check how the forms are coded

An accessible design can become inaccessible if the implementation drifts from its original design intent. Some common examples of this include

Depending on what design system you are using, there may be tools to help check for missing accessibility features or unusual patterns. For example, if you’re designing a service that will be on GOV.UK, you can use the pattern checker by Adam Liptrot to check the forms.

Consistent accessibility issues appearing in build is usually a sign of a broken feedback loop. If designs continue to become less accessible when moving into build, make sure that designers and developers are working together to have a shared understanding of accessible code.